Table of Contents

Most law students, at least in Singapore, would be familiar with the four-pronged definition of “property” from the famous 1965 Ainsworth case. Personally, it reminds me of a little jab at the definition made by one of my Property Law lecturers:

“They’re basically saying that it’s property because it’s property”.

To be honest, the most memorable part of that statement was the way it was said—kudos to the ever-venerable and wonderful Professor Teo Keang Sood. But I never seriously pondered over it. After all, it was just one of those legal musings that would never really matter. It certainly didn’t matter in the exam.

Or so I thought. As Professor Teo was defining property as property for yet another year, the Singapore courts were dealing with a massive case involving questionable programming on a cryptocurrency exchange. One of the obstacles they had to cross was the difficult question of whether cryptocurrencies were property.

Thankfully, the point wasn’t disputed, and the courts didn’t have to deal with it. But they were cautious. The High Court briefly remarked that cryptocurrencies fit within the Ainsworth definition, and the Court of Appeal laid out the literature before leaving the matter behind. The usual wise moves.

But the case finally brought the question to life: are cryptocurrencies property?

Why it didn’t matter to me, and then suddenly, it did

My immediate response to the question was, “Why should I care?” And then the law student in me awoke. Of course, I had to care.

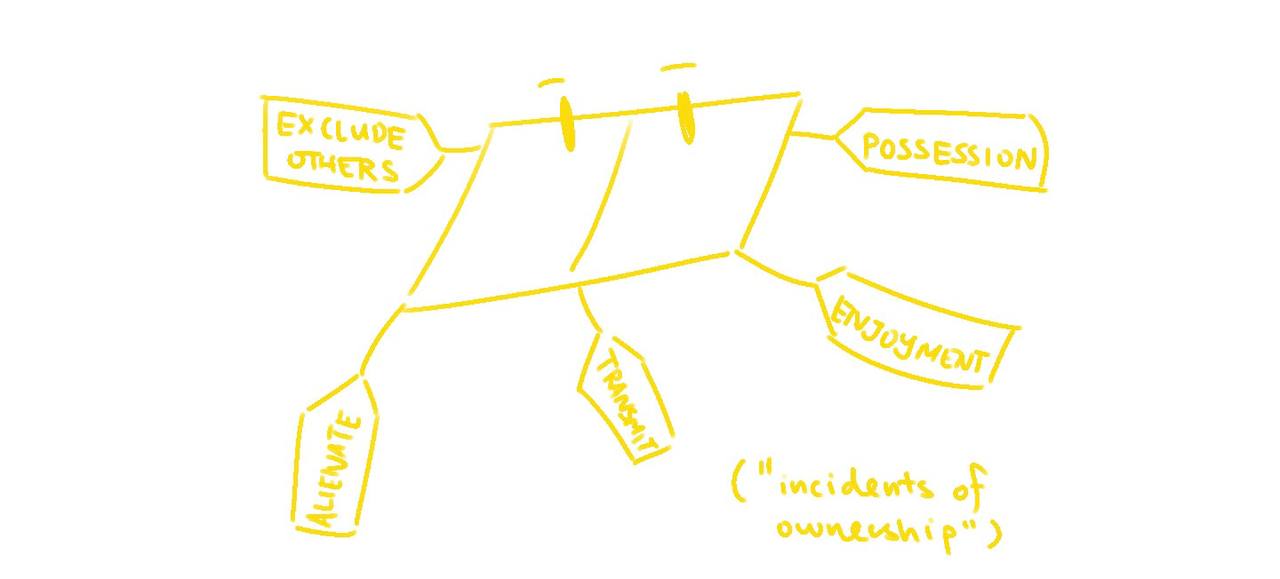

Because we know that property occupies a special place under most laws around the world. And as someone who scored a B in Property Law, I knew that the Ainsworth definition was, generally, all about third parties. The core idea of it is – and every part of this idea is hotly contested in the academic circles – property must belong to someone (technically, be “owned” by them) and keep the others out (technically, “property rights bind third parties”). A famous scholar likens it to people holding things on chains.

Put simply, if I control a property, I can stop anyone else from taking it. No one can take my phone, no one can take my house, and everyone better not take my cryptocur…

Well okay, that last part skips some steps.

What’s more important is, if something isn’t property, there’s no “me versus the world”. The classic example is information about the world, usually defined as “data” (though this is hotly contested too). Anyone can know my name, anyone can copy my ideas, and anyone can… well, take the information associated with my public key on the distributed ledger?

For what it was worth, the B-student in me saw a real problem with defining the “me versus the world” in cryptocurrencies.

How I ended up trying to code a cryptocurrency

Thankfully, I wasn’t the only one who was struggling to learn about the legal status of cryptocurrencies. The Singapore courts were assisted by the experiences of courts around the world, as well as a groundbreaking 2017 article by Professor Kelvin Low and Ernie Teo. Later on, I was assisted by an illuminating webinar by Professor David Fox at the National University of Singapore.

Ultimately, there seemed to be a common answer: “There’s property in some features of cryptocurrencies”. That was helpful, but the agreement stopped there—no one really agreed on the parts of cryptocurrencies that were “me versus the world”. And again, people don’t even agree if “property” is about “me versus the world”.

Bottomless controversies like these arise any other day in the legal world, so I mostly brushed it off. But a pandemic-imposed self-isolation period motivated me to finally take a crack at the cryptocurrency-as-property debate.

To that, some people are gifted with the ability to understand things entirely in the abstract. Not me. But I did have the privilege of being an amateur programmer.

The coding journey, with fun legal insights along the way

One of the amazing things about trying to code something in the 21st century is that free tutorials can be found everywhere. I was all over StackOverflow, YouTube, and the Bitcoin paper. At the end of about 12 hours of coding, I cleaned up and released the code for my barely functional proof-of-work cryptocurrency. And because the law student in me demanded some substantiated chunks of words, I wrote a full technical breakdown of the intuition behind the code, as well as a blog post with some broader musings about blockchains and cryptocurrencies.

For the most part, I think I reached the same conclusion as many who had done this exercise before me. In short, the technology really is quite elegant, but when it’s implemented in the real world, it raises some very real problems. As someone with a passion in copyright law, I also reached the usual conclusion on NFTs: there’s nothing new about ownership of digital content, but cryptocurrency transactions are great proof of that ownership.

But legally (read: most abstractly and annoyingly), I think this crypto-coding adventure gave me a glimpse into the true nature of cryptocurrencies. I left with the same feeling as most of the scholars who made the journey before me: there is property in some part of cryptocurrencies.

Property in some part of cryptocurrencies? What even?

The sheer abstractness of this conclusion annoyed me. It was especially humbling, because I had mentally scoffed at the academics for being so abstract. As I found myself making the same conclusion, I saw that the joke was on me.

Unfortunately, it was truly the conclusion I reached. And it’s deadly hard to explain, because it’s more of an experience than a scholarly theory. I suppose a workable analogy is as follows: you kinda know when milk turns into ice cream when you taste it, and you kinda know when random code turns into “me versus the world” when you run it.

Personally, the turning point came after coding the SHA256 puzzle for the proof-of-work mechanism. Before I did that, I could lodge new transactions onto the ledger in split-seconds (in the order of 10^-5 seconds, to be exact), and it was obvious that a fraudster could do the same across loads of accounts if they really wanted to (in technical parlance, the famed “51% attack”). Once I implemented the proof-of-work mechanism, and I saw my computer getting stalled by a lame-old guessing game, I appreciated how it would be basically impossible for the world to take what was mine.

In ice-cream parlance, proof-of-work turned the milk into ice cream. It tasted okay before, but suddenly, it tasted wonderful. And no one was going to have my ice cream. It was mine, mine, mine.

So I ended with nothing to add to the academic debate – except an experience

At the end of the day, I don’t think my crypto-coding adventure helped me to figure out the parts of cryptocurrencies which made it “property”. I just experienced the general feeling of “me against the world”. It was nothing new in light of what the scholars before me had said.

I suppose I did leave feeling more confident in following the lawyers who came before me: I quite liked the Tang and Teo “public key as the last entry” definition, as well as Professor Fox’s preliminary “composite thing, manifestation of data, and power to transact” formulation.

But as “legal” as the issue was, I was reminded that it wasn’t just the lawyers who had a say in it. The Tang and Teo piece, for example, was a brilliant mix of legalities and technicalities. I could imagine economists, business strategists and politicians having a say too.

And lest we forget, these are important issues – sure, they’re abstract as anything, but they have a real impact in our lives. Some are called to philosophize on it, some to understand the abstract interactions, and some to get their hands dirty with the technology. Wherever your place is, I hope that you may find the motivation to explore the world of cryptocurrencies – in your own way, of course.

For what it’s worth, the Singapore courts have opened a can of worms. From this point, every perspective is valuable. I hope you find your own.