Table of Contents

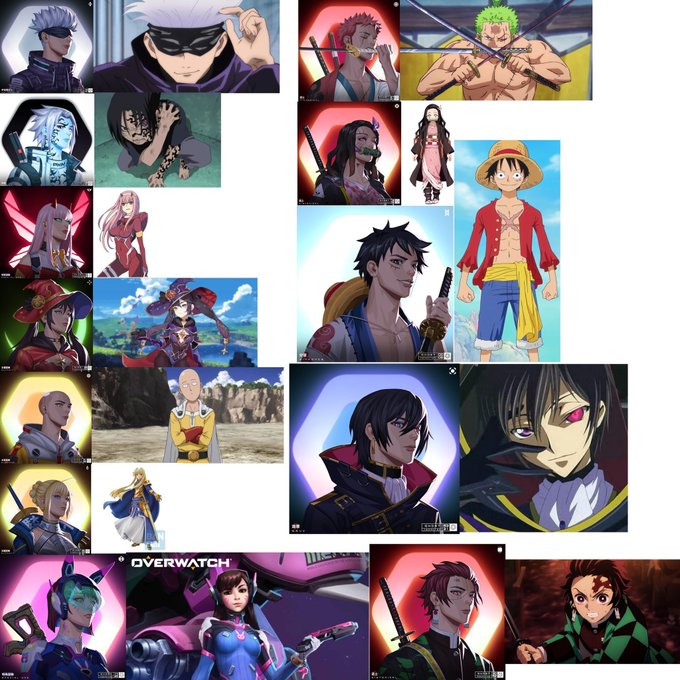

Phantom Network NFT, aka Project PXN NFT, was recently the subject of controversy over its use of various external intellectual properties (IPs) in its reveal, from anime such as Demon Slayer to video games like Overwatch. Many fans called out PXN on this, raising concerns that its NFT project could constitute an infringement of IP in the eyes of the law.

PXN promptly responded by taking down these pieces from their collection, with founder Rei Cannon pledging to replace them with another Epic or Legendary PXN original and compensate affected holders with 10 ETH per piece.

Read more: Project PXN Ghost Division NFTs Draw Flak for Anime Resemblance

IP infringement is nothing new to the NFT space, which still sees derivatives of popular projects pop up, attempting to ride on the coattails of more successful projects. Most recently, the popular Solana project Okay Bears saw a derivative, Not Okay Bears, on the Ethereum blockchain, which was taken down by Opensea within 12 hours of its launch.

Apart from derivatives, many Web2 artists have also had their art plagiarised for bogus “projects”, often having to rely on community efforts to have their stolen artwork taken down. In many ways, the NFT space is still maturing, particularly in the area of IP.

Blockhead spoke to tech lawyer Ken, who goes by LegallyBullnde on Twitter, about what constitutes IP infringement and what creators and project leads can do to protect themselves from potential lawsuits.

So, Ken, let’s jump right to it. Do you think PXN’s NFTs constitute IP infringement?

Wow, that is a hard question to answer. What we have to do is evaluate each piece against the original IP that it was inspired by. My personal take would be that some (not all) of them are not really transformative enough when compared to the original works.

For the pieces which heavily resemble redrawn in the art style of PXN, it may be justified for the studios that own these brands to make a case that PXN has infringed on their IP. Of course, at the time of this interview, I do not believe that any actual notice or claim has been issued, so let’s not speculate too much.

Some may argue that what PXN has done is no different from fan artists selling fan art art, anime, or characters at comic conventions (like Comic-Con). Assuming that these fan artists do not have expressed permission from the studios that own the characters to incorporate these characters in their art, then legally speaking, this is actually correct. To be clear, both individuals (like fan artists) and corporations can be subject to IP infringement claims. The litmus test of what constitutes IP infringement is independent of the size of the entity carrying out the act.

The litmus test of what constitutes IP infringement is independent of the size of the entity carrying out the act.

However, the parties that owners of the original IP choose to sue is a decision that may be made based on non-legal reasons. For instance, the profits that fan artists at a convention may make from selling original drawings of a well-known superhero may not amount to much at all, so the studio may decide against taking legal action against them as it would not be worth the legal fees and their brand reputation. In fact, tacitly allowing these fan artists to do so in limited circumstances may even foster goodwill between fans and the studio.

On the other hand, if it is a large and successful project that obtains widespread publicity and significant revenue, there may be a greater likelihood of being brought to court by the owners of the original IP. Suing another company is less likely to incur backlash from the public and makes much more sense financially.

In other words, as long as you are committing the act of infringement, be it as a small creator or a big corporation, you are liable to being sued in the eyes of the law.

I see. Why do you think IP infringement even happens in the first place?

In terms of legal issues, most creators I speak to usually do not give as much consideration to the legal side of things during the production process. They are more concerned with building a quality product and launching their project – this is understandable.

This is not a problem exclusive to Web3, but startups in general. Perhaps there may be a sense of urgency in trying to get the project out there or focus on preparing it for launch.

As for IP infringement specifically, I can definitely understand why some artists wish to reference external works. Some see it as a way to spread their love for the original. In PXN’s case, perhaps the creators wished to share their love for anime. Many of the characters are, after all, beloved by fans all over the world. From a more cynical point of view, some may argue that it is a way to make a quick buck off of existing IP, but I will not comment on this too much as I am not inclined to cynicism myself.

Let’s take a closer look at these terms. What does the law classify as “infringement”?

Fundamentally, infringement is not just a matter of the reproduction of an existing IP (and do note that there are different types of IP rights which I shall not get into in this interview). The crux of infringement lies in the use or reproduction of another party’s IP without the consent or permission of the original creator or owner.

There have been cases where brands incorporate other IPs legally as a form of collaboration, such as Uniqlo and their t-shirts of various anime franchises. In the case of PXN, my understanding is that they did not contact each brand before the reveal, which is what resulted in the controversy. Again, I do not believe that any of the brands actually issued any statements on this.

Before I dive further into IP law, however, it might be good to touch on what the law classifies as “intellectual property” and its purpose in the first place.

IP is a legal concept that dates back far beyond Web3; the original intention of IP laws was to give legal recognition and protection to intangible property such as art, music and research papers, in order to incentivise the creation of original works. Imagine if anything we create could be copied or imitated from the moment it is published without any consequences or repercussions; I do not think many people would feel encouraged to be original in their art or writing.

There are many types of IP rights (trademarks, patents, copyright, designs etc…), but let me focus on two aspects of IP today: copyright and trademark. In very simple terms, copyright focuses on the protection of a created work (like an artwork), while trademark focuses on the protection of a brand (or the distinctiveness of the brand). Let me explain further.

Copyright protects the creative expression of ideas, not ideas themselves. For example, the idea of a superhero may not be protected by copyright, but the specific characteristics of that superhero can be – once you create and illustrate a superhero with specific traits, powers and physical attributes, that becomes an expression of your idea that is now protected by copyright. In the case of PXN, it is not that they drew illustrations of superheroes that is an issue, but that they drew them in the likeness of specific superheroes like Saitama, or One Punch Man.

Trademark protects a company’s branding. Some examples would be Mcdonald’s golden arches or Nike’s “Just Do It” slogan. This is why in Singapore, Don Quijote is known as Don Don Donki, as a local restaurant had already laid claim to the name prior to their Singapore debut.

When you incorporate a character from an existing IP without permission (or a licence), there is a risk of copyright infringement. If the existing IP has been protected as a trademark (through registration with a trademark office), then there may also be a risk of trademark infringement.

For instance, using the One Punch Man example once again, drawing an illustration in the character’s likeness is one thing, but the studio may have also registered the character as a trademark like Disney does for some of their characters. If that is the case, then a person who has incorporated elements or a likeness of One Punch Man in their work could potentially be found to have infringed both the copyright and the trademark of the studio.

Read more: Joan Cornellà’s Stephen Chow Infringement is a Caution for NFT Artists

Furthermore, because there are different factors and tests involved in making such a decision, it could be the case that although there is no copyright infringement, there can still be trademark infringement. For example, this may occur if the work of an artist is similar enough to an existing brand’s trademark such that there is a likelihood of confusing the artist’s work to have originated from or be associated with the brand.

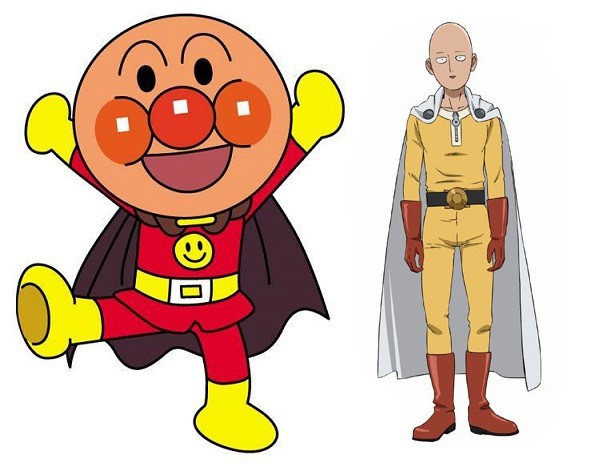

Let’s discuss that One Punch Man example. One Punch Man is actually heavily inspired by Anpanman, a Japanese children’s anime from the 70s. Does that not count as infringement given the former’s resemblance to the latter?

That is the thing, resemblance alone is not enough. From a copyright perspective, different jurisdictions usually have different thresholds, but generally, the law will not consider it infringement if the two characters are not substantially similar, or if the character in question is transformative enough such that the two works can be regarded as distinct original creations.

Remember that copyright protects only the expression of the idea, and not the idea itself.

Remember that copyright protects only the expression of the idea, and not the idea itself. From a trademark perspective, apart from the need for likeness/similarity, there must be a risk or likelihood of confusion.

Looking at Anpanman and One Punch Man, they may resemble each other in several ways, such as their outfits, but other than that, it is pretty clear to most people that they are separate characters. From their largely differing storylines to Saitama’s “one-punch” gimmick, these are factors that the court will take into consideration in its qualitative assessment of whether or not infringement has occurred.

Going back to PXN’s rendition of the hero, my personal opinion is that the referencing or incorporation of Saitama’s likeness is very clear (it feels more like a direct reproduction of him in a different art style), with little to no distinctive qualities that set their illustration apart from the original IP. Hence, there is a risk of infringement unless prior consent had been sought. That said, I do think that the PXN team has handled the situation very well, but more on that later.

That definitely gives a clearer picture of IP and its purpose. Allow me to branch into Web3 a little further. Given that NFTs and other Web3 IPs exist on-chain and across borders, how will the courts enforce IP law in such cases?

Let me focus on copyright law as an example for this question. While copyright law is jurisdiction-specific, most developed jurisdictions have a baseline standard for what can be protected, and what counts as infringement. In general, if your work is protected in one jurisdiction, it is likely to be protected elsewhere, making it easier to make a case across different regions.

For cross-border disputes, the good news is that many countries have reciprocal arrangements to protect copyright across different jurisdictions, such as the Berne Convention and the TRIPS Agreement, the latter of which is agreed upon by all members of the World Trade Organisation. These agreements allow IP owners of one country to enforce copyright in another if both countries operate within these frameworks. However, if the infringing party is in a jurisdiction that is not a party to any such reciprocal arrangements, then, unfortunately, you will have to follow the laws of that jurisdiction if you want to enforce a claim against that party.

The other issue to note is that, while you may be able to get a judgment or order against an infringing party, there will likely be practical difficulties in enforcing it. For example (and forgive me if my understanding is inaccurate), if something is minted on a blockchain, the only way for it to be taken down is for the current owner to burn it. But this is only workable if the current owner is doxxed, which, especially in Web3, is not always the case.

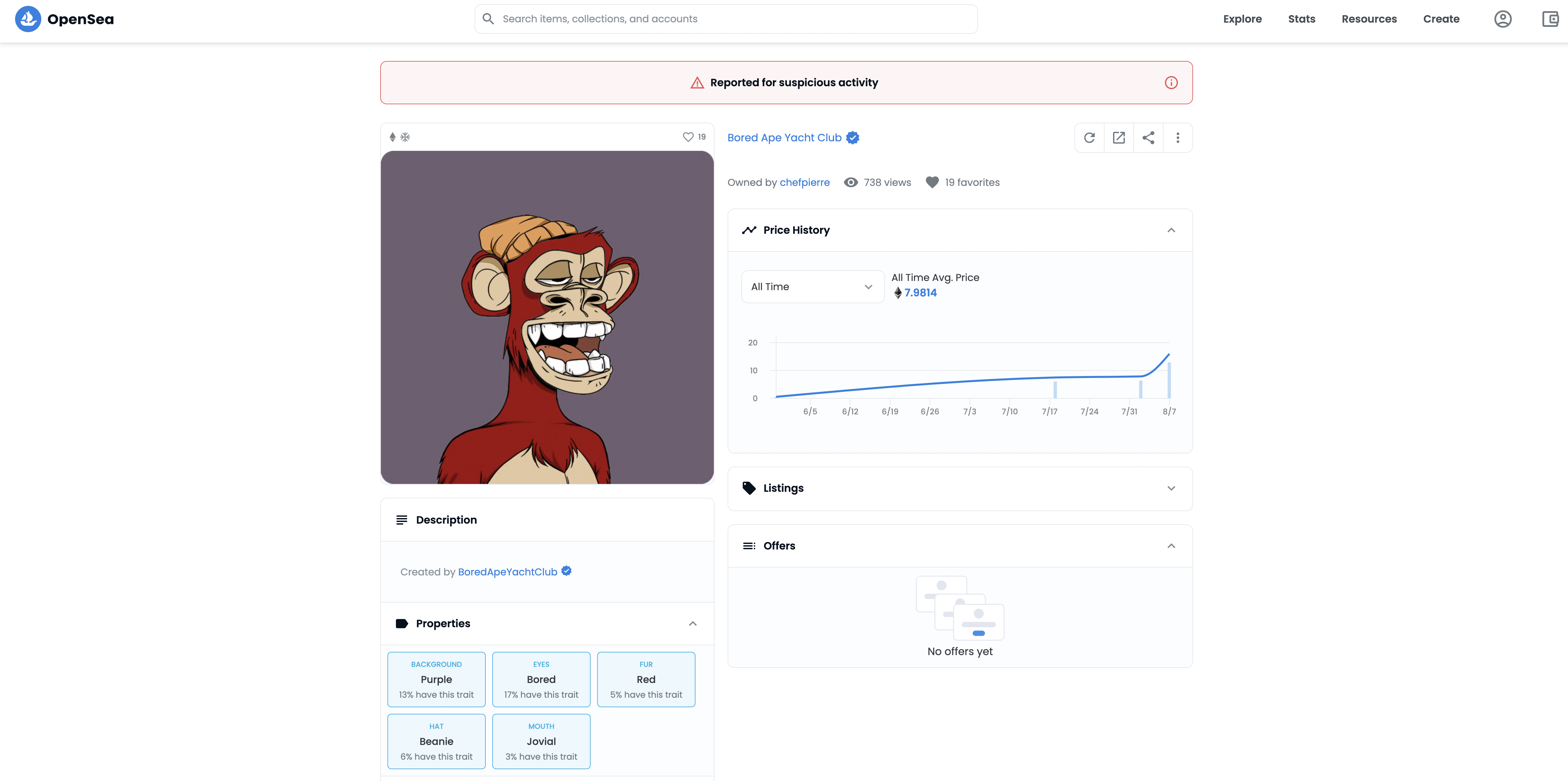

Metamask does not require KYC, and while Opensea, a centralised website, can take down collections if the court requests them to, the NFT will still exist and be capable of being traded and sold privately, or in other marketplaces that are not willing to comply.

Alternatively, because an NFT is distinct from the underlying artwork, you can also try to find out where the server hosting the metadata of the underlying artwork is stored (such as the InterPlanetary File System, or IPFS) and request for the images stored there to be taken down. But again, this may not always be practically workable.

For instance, while the Singapore High Court recently blocked the transfer of Bored Ape (BAYC) 2162, it remains to be seen how the court will enforce this decision. They could request for Opensea and other marketplaces to delist it, but the Ape would still exist on the Ethereum blockchain.

Enacting a civil suit on the current holder would require them to be doxxed, and while there are methods to doxx someone involuntarily, such as tracking the user’s IP (Internet Protocol) address, the processes do not guarantee success, and will likely be laborious, lengthy and expensive. There is also no guarantee they exist within a jurisdiction that will uphold a judgment/order issued by the Singapore High Court.

While the case of BAYC 2162 is not a case of IP infringement, the problems of enforcement of a legal judgement are nonetheless the same. Decentralisation, with all its advantages and benefits, also comes with its own set of problems; the struggle to enforce legal authority over Web3 is one of them.

In that case, how do you see the issue of IP in Web3 being handled in the law in years to come? Are there any areas the law needs to adapt to?

Moving forward, the concept of IP will definitely still remain. Nothing about IP has fundamentally changed over the past few centuries, whether the works were created on a canvas or an iPad. While some in Web3 believe that all Web3 works should exist under a Creative Commons Public Domain licence (i.e. CC0), I think we need to first understand that even a CC0 license exists under the framework of IP law.

I think we need to first understand that even a CC0 license exists under the framework of IP law.

The true intent and purpose of IP law is to recognise creators’ rights over their works and give them the flexibility to decide if they want their works to be publicly available for reproduction. This allows creators to grant their users, collectors or viewers different permissions for what they can do with the work. As a creator, you are free to choose between “All Rights Reserved” (which is the strictest position and also applies by default unless you have otherwise indicated), a CC0 or Public Domain licence, and anywhere in between.

Having said that, I believe the law needs to catch up on three fronts. Firstly, as mentioned, it will be interesting to see how courts deal with judging cases involving anonymous parties, which are increasingly common in Web3. Secondly, with greater globalisation of economic and peer-to-peer activity in Web3, there may be a greater need for standardised law across various jurisdictions around the world. This has historically been rather difficult, but perhaps Web3 may give sufficient motivation to expedite this trend.

Read more: Are Digital Assets Property? Singapore Courts Say Yes in Landmark Ruling

Lastly, the law will need to figure out how to deal with fractionalised ownership of IP in the form of Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs). The conventional concept of co-ownership of IP was formulated during a time when co-ownership was limited to smaller groups of people.

Currently, the law is ill-equipped to address a scenario where, potentially, thousands of people in a DAO or governance protocol may “own” the IP of a particular work. This probably does not sit comfortably with existing law and will be something that courts and legislators will need to adapt to in the future.

What about creators? What advice do you have for creators to protect themselves and their creations legally?

My main piece of advice would be to take a step back and consider what could go wrong not just from a financial or marketing perspective, but from a legal perspective as well. Starting off with a good foundation is also important.

You do not necessarily need to hire lawyers and incur costs at the outset; there are many resources freely available online for you to use. The important thing is to educate yourselves so that you are making informed decisions and/or calculated risks.

With respect particularly to IP issues, it definitely helps to learn and recognise what the different types of IP and protected rights are (e.g. copyright, trademarks etc…), what they are intended to protect, and the do’s and don’ts of IP. To prevent infringement, do some basic due diligence (for example, Google search phrases, logos, or designs that you may wish to incorporate into your brand, just to check that they are not already used by other entities). If you wish to reference other works, I would suggest asking the original creators for permission and seeking written approval where possible. Conversely, if you are hoping to create something original yourself, you can use existing legal frameworks to protect your project, such as trademarking your brand name or identity.

I would also advise creators to make it clear to holders and collectors what they actually own when they buy your NFTs, and what they are allowed to do with the underlying artwork (i.e. if they can reproduce it, commercialise it etc…).

Read more: Are You Really the Owner of Your NFTs?

Again, when in doubt, you may wish to assume that the creator has licensed it on an “All Rights Reserved” basis (which is the default position under the law). Hence, letting holders know what they own in the fine print definitely helps prevent any confusion between holders and creators and is generally good practice. You can do so by adding proper terms and conditions in your project website.

Any final thoughts on PXN and the way they handled things?

I would definitely like to commend the way they addressed the controversy so swiftly, taking action almost immediately. While many other projects would have dismissed the criticism as FUD, the founder, Rei Cannon was quick to nip the issue in the bud and compensate all affected parties.

From a legal perspective, what they did was responsible to their holders, and from an artist’s perspective, it was respectful to the original IP. I believe that such projects will be the ones to survive and last through tumultuous bear market conditions, and I am excited to see what they do next.

The article and all contents provided above is for general information and educational purposes only, and should not be deemed or relied upon as professional or legal advice. Concepts and discussions may also have been simplified for ease of understanding and do not capture the full nuances or complexities of the relevant subject matter. Please consult a legal professional if you require formal legal advice or assistance.

For more information on the legal issues projects may face, read Ken’s Twitter thread here.